Critiques

Né en 1953, Mike Bidlo est un artiste américain qui a fait ses classes à Columbia et à l’université de l’Illinois de Chicago. Il pratique la peinture, la sculpture et la performance. Mike Bidlo, considéré comme un artiste post moderne, a bâti sa carrière sur la « re » création et l’appropriation des œuvres d’autres artistes, reproduisant le travail de chacun. La particularité des reproductions de Bidlo c’est qu’elles cherchent à imiter précisément, exactement, l’image, l’échelle et les matériaux de leur source. D’autre part, Bidlo ne travaille pas à partir de l’original de l’œuvre, mais à partir de reproductions de l’original, ce qui rend ses pièces deux fois retirées de leur source.

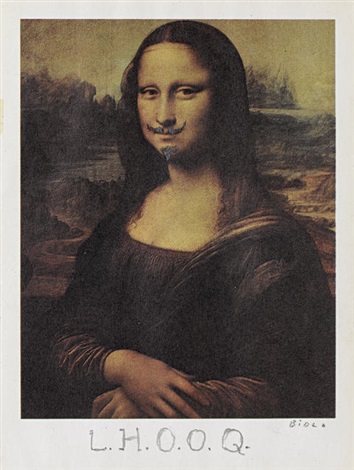

Mike Bidlo est un artiste qui appartient au courant que l’on nomme Appropriationniste (artistes apparus au début des années 80 qui misent sur la prise de possession par la copie des œuvres d’autrui.) (1) C’est un mouvement qui reste informel (on n’a pas de manifeste) mais qui a tout de même un objectif : la remise en cause des notions d’ « auteur », d’ « originalité », de « nouveauté », si chères à l’Art depuis la Renaissance.(2) ![]() Si Bidlo considère sa démarche artistique comme politique, nous allons voir qu’elle est aussi ontologique.

Si Bidlo considère sa démarche artistique comme politique, nous allons voir qu’elle est aussi ontologique.

(1) La citation, l’emprunt, existe dans l’Histoire de l’Art depuis ces commencements. Les romains ont bien imités les copies grecques des oeuvres, Manet s’est inspiré de Titien pour peindre l’Olympia, Braque comme Picasso s’inspirent largement des Arts premiers au cours de la période cubiste, Marcel Duchamp empreinte au réel et ne fait que déplacer des objets de contexte puis les signe dans ses ready-mades. Les appropriationnistes se situent dans une ligne logique d’interrogations sur toutes ces notions d’auteur, plagiat, copie, inspiration, emprunt, mention, etc. Mais dans un sens bien plus radical.

(2) Avant la Renaissance, au Moyen-Age donc, on considère que le seul auteur est Dieu. Et les écrivains penseurs poètes etc. retranscrivent par écrit la pensée divine mais en aucun cas peut-on considérer qu’il existe un tiers auteur que le Créateur. Pour aller plus loin : Paul Vignaux. Philosophie au Moyen-Age. Vrin, 2004.

![]() Born in 1953, Mike Bidlo is an American artist who studied at Columbia and at the Illinois university of Chicago. He practices painting, sculpture and performance. Mike Bidlo, considered a post-modern artist, has built his career on the « re » creation and appropriation of the works of other artists, reproducing the work of each. The peculiarity of Bidlo’s reproductions is that they seek to imitate precisely, exactly, the image, the scale and the materials of their source. On the other hand, Bidlo does not work from the original of the work, but from reproductions of the original, which makes his pieces twice removed from their origin.

Born in 1953, Mike Bidlo is an American artist who studied at Columbia and at the Illinois university of Chicago. He practices painting, sculpture and performance. Mike Bidlo, considered a post-modern artist, has built his career on the « re » creation and appropriation of the works of other artists, reproducing the work of each. The peculiarity of Bidlo’s reproductions is that they seek to imitate precisely, exactly, the image, the scale and the materials of their source. On the other hand, Bidlo does not work from the original of the work, but from reproductions of the original, which makes his pieces twice removed from their origin.

Mike Bidlo is an artist who belongs to what we call Appropriationism (artists appeared in the early 80s who bet on taking possession by copying the works of others.) (1) It’s a movement that remains informal (we does not have a manifesto) but which nevertheless has an objective: questioning notions of « author », « originality », « novelty », so dear to Art since Renaissance. (2) ![]() If Bidlo considers his artistic approach as political, we will see that it’s also ontological.

If Bidlo considers his artistic approach as political, we will see that it’s also ontological.

(2) Before the Renaissance, in the Middle Ages, it was considered that the only author was God. And writers thinkers poets etc. transcribed divine thought in writing but in no case can we consider that it exists an author other than the Creator. To go further: Paul Vignaux. Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Vrin, 2004.

Bidlo est sans doute l’artiste le plus dénué d’identité visuelle. Lorsqu’on l’interroge sur les raisons qui l’ont poussé à adopter l’appropriation comme méthode, il met en avant des motivations politiques. L’appropriation, selon lui, doit permettre de diffuser la culture à travers toutes les classes de la société, y compris les classes les plus défavorisées. L’artiste indique en effet que les chefs-d’œuvre de l’art moderne, victimes de leur sacralisation, restent trop souvent cachés chez leur propriétaire, ou dans des musées souvent hors de portée, voire dans des pays étrangers.(3)

Les faire voyager dans des expositions reste une solution peu utilisée, dans la mesure où leur déplacement implique des frais importants, et le risque de vol ou dégradation se voit multiplié. Bidlo entend bien faire changer cette situation. L’une des œuvres de Bidlo est intitulée Un poulet dans chaque marmite et un Pollock dans chaque salon. (4) Ce titre pourrait, de toute évidence, servir de formule à son action. L’ambition de Bidlo est donc simple : il s’agit avant tout de (re-)produire les chefs-d’œuvre pour les diffuser largement, et les vendre à moindre frais. Ses copies sont généralement vendues au prix de 10 000 euros.

Bidlo met parfois en scène le partage égalitaire de l’art dans des performances en distribuant littéralement des parts de ses œuvres. Notamment avec Painting Blue Poles (5), une performance qui a eu lieu sur les marches du Metropolitan Museum de New York en 1982 où une fois l’œuvre réalisée, le plasticien a divisé la peinture en petits morceaux qu’il a ensuite distribué au public. (6) Quelque peu utopiste, on ne peut que rétorquer que la copie existait avant le mouvement Appropriationniste et que l’interroger relance les débats en Histoire de l’Art de multiples manières.

Comme il le confiait en 2010 au New-York Times à Nadine Rubin Nathan : « Si vous voulez devenir aussi grand que Warhol l’a été dans le domaine de l’art, alors vous devez avoir des générations plus jeunes qui explorent votre travail et essaient de le comprendre comme un langage. » (7) En cela le projet semble assez réussi puisque ses oeuvres ne cessent de questionner jeunes plasticiens et théoriciens.

(3) Selon le philosophie italien marxiste Gramsci, lutte culturelle et lutte sociale vont de pair. L’accès à l’art cristallise les injustices sociales d’une époque. Voir Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni dal Carcere. Einaudi, 2014.

(4) Cette performance est une citation directe à un slogan de 1928 du président américain en devenir Herbert Hoover (en poste de 1929 à 1933 pendant la Grande Dépression) : « Un poulet dans chaque marmite et deux voitures dans chaque garage ». Ce slogan a d’autant plus marqué l’imaginaire américain qu’Hoover était d’origine très modeste et très vite orphelin. Faisant fortune dans l’industrie minière, il incarne à merveille le rêve américain. Voir « A Chicken for Every Pot, » The New York Times, 30 October 1928

(5) de Blue Poles, 1952 oeuvre de Jackson Pollock. Huile, émail, peinture aluminium, verre sur toile, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Sous licence ARS/Copyright Agency.

(6) L’Appropriationnisme tâche de court-circuiter cela en reproduisant au strict identique des chefs-d’oeuvres de l’Histoire de l’Art et ainsi mettre à mal le monde de l’art, rendant caduque le marché des oeuvres uniques, tout en faisant vaciller la signification de l’Oeuvre.

(7) https://archive.nytimes.com/tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/02/asked-answered-mike-bidlo/?_r=0

![]() Bidlo is arguably the artist most devoid of visual identity. When asked about the reasons that led him to adopt appropriation as a method, he puts forward political motivations. Appropriation, according to him, must allow culture to be spread across all classes of society, including the most disadvantaged classes. The artist indicates in fact that masterpieces of modern art, victims of their sacralization, too often remain hidden with their owner, or in museums often out of reach, or even in foreign countries.

Bidlo is arguably the artist most devoid of visual identity. When asked about the reasons that led him to adopt appropriation as a method, he puts forward political motivations. Appropriation, according to him, must allow culture to be spread across all classes of society, including the most disadvantaged classes. The artist indicates in fact that masterpieces of modern art, victims of their sacralization, too often remain hidden with their owner, or in museums often out of reach, or even in foreign countries.

Having them travelling in exhibitions remains a solution that is little used, since their displacement involves significant costs, and the risk of theft or degradation is multiplied. Bidlo intends to change this situation. One of Bidlo’s works is titled A Chicken in Each Pot and a Pollock in Each Living Room (4). This title could obviously serve as a formula for his action. Bidlo’s ambition is therefore simple: above all, it is a question of (re) producing masterpieces in order to distribute them widely, and sell them at low cost. Its copies are generally sold at a price of 10,000 euros.

Bidlo sometimes stages the egalitarian sharing of art in performances by literally distributing shares of his works. Notably with Painting Blue Poles (5), a performance which took place on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1982 where once the work was completed, the visual artist divided the painting into small pieces which he then distributed to the audience. (6) Somewhat utopian, we can only retort that the copy existed before the Appropriationist movement and that questioning it revives debates in Art History in multiple ways.

As he told the New York Times in 2010 to Nadine Rubin Nathan: « If you want to become as big as Warhol became in the field of art, then you have to have younger generations exploring your work and try to understand it as a language. » (7) The project seems quite successful since its works continue to question young visual artists and theorists.

(3) According to the Italian Marxist philosopher Gramsci, cultural struggle and social struggle go hand in hand. Access to art crystallizes the social injustices of an era. See Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni dal Carcere. Einaudi, 2014.

(4) This performance is a direct quote from a 1928 slogan of future US President Herbert Hoover (in office from 1929 to 1933 during the Great Depression): « A chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage ». This slogan had all the more impact on the American imagination because Hoover was of very modest origin and very quickly became an orphan. Making his fortune in the mining industry, he perfectly embodies the American dream. See “A Chicken for Every Pot,” The New York Times, October 30, 1928

(5) From Blue Poles, 1952 work by Jackson Pollock. Oil, enamel, aluminum paint, glass on canvas, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Licensed by ARS/Copyright Agency.

(6) Appropriationism attempts to short-circuit this by reproducing masterpieces of Art History exactly identically and thus undermine the world of art, making the market for unique works obsolete, while making the meaning of the Work waver.

(7) https://archive.nytimes.com/tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/02/asked-answered-mike-bidlo/?_r=0

- © Not de Chirico (Metaphysical Interior with Workshop, 1948), 1989 – 1990

- © Not Picasso (Self-Portrait: Yo Picasso, 1901), 1986

- © Not Warhol (Marilyn), 1984

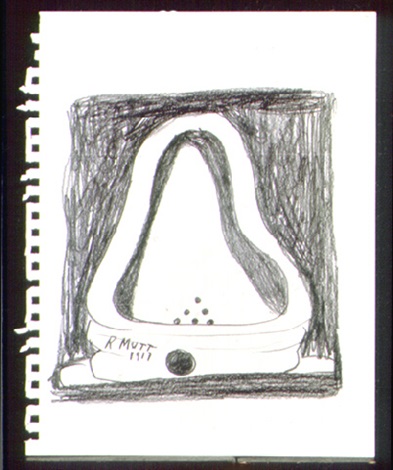

- © The Fountain Drawings (#1886 from the , 1993 – 1997

© (Not) Duchamp’s, 1987

Bidlo est de tous les appropriationnistes celui qui s’apparente le plus à un faussaire. Ses œuvres sont des copies conformes des originaux. Dans son travail, on se retrouve face à un degré zéro d’invention. Pour autant, ses œuvres peuvent être interprétées comme une célébration de la disparition de la notion d’auteur. Après la course effrénée à la nouveauté, à la rupture, constatée notamment au début du XXe siècle dans les Avant-gardes (8), avec Bidlo, le temps semble être suspendu. C’est un peu comme si la recherche du nouveau, qui avait été un des éléments moteurs de la Modernité, venaient soudainement buter sur l’évidence de l’épuisement des possibles en matière d’invention artistique.

Bidlo, lors de ses reproductions, titre ses œuvres en plaçant un « not » devant le nom de l’artiste qu’il copie. Le titre fait figure ici d’acte de destitution signifiant que les formes appartiennent à tout le monde et pas seulement aux artistes qui les ont signées. Le « not » suivi d’un nom d’auteur induit l’idée que le premier auteur de l’œuvre ne saurait revendiquer la pleine et entière paternité des images et des styles que Bidlo, ou un autre, redonne à voir.

On peut aussi comprendre ce que « not » remet en question dans le statut de l’artiste. Picasso, par exemple, n’a pas inventé Les Demoiselles d’Avignon ex nihilo comme on l’a vu plus haut. Il a mis à profit sa connaissance conjointe de la statuaire ibérique primitive et des masques congolais de façon à les intégrer dans une composition relativement unifiée. Jusqu’à une date récente, peu d’artistes, néanmoins, ont accepté de reconnaître leur dû. Pourtant, une toile c’est avant tout le résultat de tout ce qui a été créé précédemment, et à partir de quoi l’artiste va créer à son tour.

En intitulant « Not Picasso » une œuvre qui ressemble très précisément à un Picasso, Mike Bidlo ouvre en quelque sorte l’œuvre à l’altérité qui l’habite ; il invite le spectateur à dresser l’inventaire des emprunts à travers lesquels l’œuvre s’est constituée. On est ici dans un questionnement ontologique. Peut-on considérer une œuvre indépendamment de l’artiste qui l’a créé ? Est-ce que l’œuvre a une vie indépendamment de son créateur ? Quels artefacts précèdent le surgissement, la création d’un autre et quelle valeur leur apporter ? Le titre que leur confère Bidlo vient en tout cas lever le doute sur l’attribution et la valeur de reconnaissance de dette, ainsi que sur la vie d’une œuvre qui ne saurait se limiter à une simple exécution première.

(8) Le changement en art est condition créative, l’Art ne saurait se satisfaire du retour du même. C’est ainsi que l’on rompt avec la tradition et épouse la Modernité. Ajoutons d’Arthur Rimbaud (« poète d’une civilisation non encore apparue » d’après René Char : « Il faut être absolument moderne. » Une Saison en Enfer, Rimbaud, Oeuvres, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 1960. p. 241. René Char, Recherche de la Base et du Sommet, Paris, Gallimard, 1965, p. 102.

![]() Bidlo is of all the appropriationists the one who most closely looks like a forger. His works are exact copies of the originals. In his work, we find ourselves facing a zero degree of invention. However, his works can be interpreted as a celebration of the disappearance of the notion of author. After the frantic race for novelty, for rupture, noted notably at the beginning of the 20th century in the Avant-gardes (8), with Bidlo, time seems to stand still. It’s a bit as if the search for the new, which had been one of the driving forces of Modernity, suddenly came up against the evidence of the exhaustion of possibilities in terms of artistic invention.

Bidlo is of all the appropriationists the one who most closely looks like a forger. His works are exact copies of the originals. In his work, we find ourselves facing a zero degree of invention. However, his works can be interpreted as a celebration of the disappearance of the notion of author. After the frantic race for novelty, for rupture, noted notably at the beginning of the 20th century in the Avant-gardes (8), with Bidlo, time seems to stand still. It’s a bit as if the search for the new, which had been one of the driving forces of Modernity, suddenly came up against the evidence of the exhaustion of possibilities in terms of artistic invention.

Bidlo, during reproductions, titles his works by placing a « not » in front of the artist’s name which it copies. The title appears here as an act of dismissal meaning that the forms belong to everyone and not only to the artists who signed them. The « not » followed by an author’s name induces the idea that the first author of the work cannot claim the full and entire authorship of the images and styles that Bidlo, or anyone else, put back in sight.

We can also understand what « not » questions regarding the status of the artist. Picasso, for example, did not invented Les Demoiselles d’Avignon ex nihilo as we understood in the introduction. He made use of his joint knowledge of primitive Iberian statuary and Congolese masks so as to integrate them into a relatively unified composition. Until recently, few artists, however, have agreed to acknowledge their due. However, a canvas is above all the result of everything that has been created previously, and from which the artist will create in turn.

By titling « Not Picasso » a work that very precisely looks exactly like a Picasso, Mike Bidlo in a way opens the work of art to the otherness that inhabits it; he invites the viewer to draw up an inventory of the loans through which the work was built up. We are here in an ontological questioning. Can we consider a work independently of the artist who created it? Does the work have a life independently from its creator? What artifacts precede the emergence, the creation of another and what value can be brought to them? The title that Bidlo gives them comes in any case to remove the doubt about the attribution and has value of acknowledgment of debt, as well as on the life of a work which cannot be limited to a simple first execution.

(8) Change in art is a creative condition, Art cannot be satisfied with the return of the same. This is how we break with tradition and embrace Modernity. Let us add from Arthur Rimbaud (« poet of a civilization that has not yet appeared » according to René Char: « One must be absolutely modern. » Une Saison en Enfer, Rimbaud, Oeuvres, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 1960. p. 241. René Char, Research of the Base and the Summit, Paris, Gallimard, 1965, p. 102.

© Not Pollock, 1980 – 1989

Arrêt sur une œuvre (DRIPPINGS de Pollocks) : Contrairement aux autres œuvres de Bidlo, les « Not Pollock » ne sont pas des copies traits pour traits. Il s’agit plutôt d’une sorte de remake improvisé. L’artiste a travaillé une année entière pour arriver à saisir le geste de Pollock, s’aidant des vidéos d’Hans Namuth. (9)

« Ce n’est pas aussi simple qu’il y paraît. J’ai beaucoup pratiqué. J’ai traqué autant de Pollock réels qu’il était possible de trouver de façon à examiner de près comment ils avaient été réalisés. En essayant de reproduire la gestuelle de Pollock, j’ai découvert que sa ligne était une sorte de calligraphie cursive qui pouvait être apprise comme la méthode Palmer. Après un an d’essais et d’erreurs, j’ai appris à contrôler la viscosité, la disposition en couches successives et les différentes façons selon lesquelles la peinture frappe et est absorbée par la surface de la toile ». (10)

Il faut noter que Bidlo a dû négocier avec les réalités du XXème finissant. Les couleurs utilisées par Pollock ne sont plus commercialisées. Et il faut donc les imiter par d’autres moyens : « Etant donné que le Duco n’est plus commercialisé, j’ai dû avoir recours à une peinture à l’émail achetée à la quincaillerie et j’ai dû reconstituer de façon approximative la palette de chaque peinture de Pollock ». (11)

L’intérêt d’une réactivation des drippings (12) de Pollock se trame dans une relecture : au moment où Pollock a présenté ses premiers drippings, le style dominant en Amérique était une sorte de Cubisme Synthétique, (13) ou de surréalisme finissant. Ceux-ci formaient donc la toile de fond du champ énonciatif dans lequel devait intervenir Pollock. En marge des « énoncés » de Pollock, il y avait aussi l’expressionnisme abstrait naissant (Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, etc.) Lorsque Bidlo réactive les œuvres de Pollock, le champ énonciatif a totalement changé.

C’est cette fois le néo-expressionnisme de Schnabel (14) qui est dominant. Dans l’intervalle de temps séparant Pollock de Bidlo, il y a eu le Pop Art, le Minimalisme, l’Art Conceptuel et ceux-ci viennent interférer avec la lecture que l’on peut faire du dripping. Force est donc de faire de « Not Pollock » une lecture contextuelle : on peut voir en lui une critique du Néo-Expressionnisme de Schnabel qui resservait à cette époque les poncifs de l’expressionnisme.

Alors que le Pollock original était une apologie de la créativité libéré de toutes entraves formelles européennes, l’œuvre de Bidlo semble tourner en dérision la spontanéité expressionniste en la répétant. Une même forme peut donc véhiculer des sens totalement opposées dès lors qu’elle est remise en scène à des moments différents de l’histoire. La difficulté avec ce type de travail et, partant, ce qui fait son intérêt et ses limites, tient au contraste théorique entre ce que le discours appropriationniste définit comme critique en pratique des notions d’auteur et d’originalité (comme garanties traditionnelles de la valeur marchande et symbolique des œuvres).

Et l’évidence du statut allégorique de leurs œuvres, comme l’a démontré en 1980 Craig Owens: « Les manipulations auxquelles ces artistes soumettent ces images visent à les vider de leur résonance, de leur signification, du sens qu’elles revendiquent de façon autoritaire (…) Si sa pratique résulte d’un vide dans le champ des possibles de la création, d’une certaine manière elle les vide aussi de leur aura, et de leur signification première. (15) Voir peut être de leur intérêt même ?

Alors, crise de l’aura? Oui, si cette notion définit et est définie par le caractère unique, authentique et original, reconnu dans la matérialité et le mode d’exposition spécifiques à une œuvre d’art, ce qui n’est plus le cas dans sa reproduction dégradée et/ou redimensionnée et ré-encadrée. Non, car dans le même temps l’œuvre originale existe toujours matériellement quelque part et n’est pas en soi dégradée, à moins qu’on ne réduise son existence et son éventuelle portée à toutes ses reproductions- dégradations et à tous ses usages. Ce serait donc uniquement sur le plan de l’image que l’affaire se jouerait ?

(9) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cgBvpjwOGo

(10) « Mike Bidlo talks to Robert Rosenblum », Artforum International, vol.XLI, n°8, avril 2003.

(11) Ibid.

(12) https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/dripping/26815

(13) Le cubisme synthétique se caractérise par une plus grande utilisation de la couleur mais aussi l’ajout de divers collages, papiers, objets, dépassant le stricte cadre du bidimensionnel.

(14) Peu connu en France, pour aller plus loin : https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/programme/agenda/evenement/cj6eLg

(15) Craig Owens, « The Allegorical Impulse : Towards a Theory of Postmodernism », October, n°12, printemps 1980.

![]() Stop on a work (DRIPPINGS by Pollocks): Unlike the other works by Bidlo, « Not Pollock » are not line copies for lines. It’s more like an improvised remake. The artist worked an entire year to capture Pollock’s gesture with Hans Namuth videos. (9)

Stop on a work (DRIPPINGS by Pollocks): Unlike the other works by Bidlo, « Not Pollock » are not line copies for lines. It’s more like an improvised remake. The artist worked an entire year to capture Pollock’s gesture with Hans Namuth videos. (9)

« It is not as simple as it seems. I have practiced a lot. I have tracked down as many real Pollocks as I could find so as to take a close look at how they were made. Trying to reproduce Pollock’s gestures, I discovered that his line was a kind of cursive calligraphy that could be learned like the Palmer method. After a year of trial and error, I learned to control the viscosity, the arrangement in successive layers and the different ways in which the paint strikes and is absorbed by the surface of the canvas. » (10)

It should be noted that the artist had to negotiate with the realities of the late twentieth century. The colors used by Pollock are no longer sold. And so you have to imitate them in other ways: « Since the Duco is no longer sold, I had to use an enamel paint purchased from the hardware store and I had to roughly reconstruct the palette of each Pollock paint. » (11)

The interest of a reactivation of Pollock drippings (12) is woven into a re-reading: at the time when Pollock presented his first drippings, the dominant style in America was a kind of Synthetic Cubism, (13) or ending surrealism. These therefore formed the backdrop for the enunciative field in which Pollock was to intervene. In addition to Pollock’s statements, there was also emerging abstract expressionism (Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, etc.) When Bidlo reactivates Pollock’s works, the enunciative field has completely changed.

In this time it was Schnabel’s neo-expressionism (14) that was dominant. In the time between Pollock and Bidlo, there has been Pop Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art and these interfere with the reading that can be done with dripping. It’s therefore necessary to make « Not Pollock » a contextual reading: we can see in it a critique of Schnabel’s Neo-Expressionism which at that time remade clichés of expressionism.

While the original Pollock was an apology for creativity freed from all formal European shackles, Bidlo’s work seems to mock expressionist spontaneity by repeating it. The same form can therefore convey completely opposite meanings as soon as it is re-staged at different times in history. The difficulty with this type of work and, therefore, what makes it interesting and its limits, is due to the theoretical contrast between what, for example, the appropriationist discourse defines as critical in practice of the notions of author and originality (as traditional guarantees of the market and symbolic value of the works).

And the evidence of the allegorical status of their works, as demonstrated in 1980 by Craig Owens: « Manipulations to which these artists submit these images aim to empty them of their resonance, of their meaning, the meaning they claim in an authoritarian way (…) If its practice results from a void in the field of creation possibilities, in a certain way it also empties them of their aura, and of their primary meaning. » (15) Maybe from their own interest too ?

So, is it an aura crisis? Yes, if this notion defines and is defined by the unique, authentic and original character, recognized in the materiality and the mode of exposure specific to a work of art, which is no longer the case in its degraded reproduction and / or resized and re-framed. No, because at the same time the original work still exists materially somewhere and is not in itself degraded, unless we reduce its existence and its possible scope to all its reproductions-degradations and to all its uses. It would therefore be only in terms of image that the case would play out ?

(9) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cgBvpjwOGo

(10) « Mike Bidlo talks to Robert Rosenblum », Artforum International, vol.XLI, n°8, avril 2003.

(11) Ibid.

(12) https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/dripping/26815

- © Untitled (not Pollock),1983

Hey! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new apple iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the outstanding work!

It was an excellent article! Appreciate it for providing your knowledge.